Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

Some people keep their nose to the grindstone, their ear to the ground, or their eye on the ball. But the roseate spoonbill keeps its bill in the muck. The beautiful bird feeds by sticking its wide, spoon-shaped bill into murky waters and sweeping it from side to side. The inside of the bill is lined with sensitive detectors that feel the vibrations of small fish, shrimp, insects, or other possible prey. When it feels one of these tasty morsels, the bird snaps its bill shut, then uses the bill to separate the good bits from the mud and debris.

Don’t tell anyone else, but we know where you can find a fortune in gold -- about 20 million tons of it. It’s in the oceans. Not in sunken pirate ships or Spanish galleons, but dissolved in the water itself.

In fact, ocean water is like a well-stocked chemical warehouse. About three-and-a-half-percent of it consists of molecules of something other than H-2-O.

Getting to know all the fish in the seas is a tough job. There’s a lot of ocean to cover, after all, and many species aren’t especially easy to find -- they have limited numbers or range, or they lurk in waters that aren’t often explored.

An example is the frilled shark. It looks almost nothing like most other shark species. Its body is long and sinuous, like an eel’s, and its head looks more like a snake than a fish. It has a prehistoric look, which is appropriate, since its ancestors were around at least 80 million years ago.

A few years back, McDonald’s tried a change in the way it packaged its burgers. They were separated to keep the hot ingredients hot and the cold ingredients cold. And there seems to be a similar separation in the oceans. The warm upper layers seem to be getting warmer than thought, while the cold lower layers don’t seem to be getting any warmer at all.

About 90 percent of the extra heat created by global warming goes into the oceans. But tracking just where that heat is going is a tough job.

The geographic cone snail was already known as a quiet killer. It’s only a few inches long. And like many other species of cone snail, it lurks at the bottom of warm, shallow waters near coral reefs, sometimes burying itself beneath sand and pebbles. It waits until an unwise fish swims close by, then zaps it with a small “harpoon” laced with a powerful neurotoxin. The fish is paralyzed in seconds, ready for the snail to pull it in and swallow it whole.

In Greek mythology, the Argo was a ship that carried Jason and his band of heroes on adventures through unknown waters. Today, another Argo is exploring unknown waters. In fact, it’s turning the un-known into the known.

This Argo is an international project that’s measuring ocean conditions down to depths of almost a mile. It consists of more than 3800 probes that measure temperature, salinity, and currents in all the world’s oceans.

Many species of marine life are changing addresses. As the oceans get warmer, they’re moving to new waters to seek out comfortable temperatures. But quite a few species of fish could be about to make a really big move -- from the north Atlantic to the north Pacific or vice versa. That could mean big changes for the ecosystems of both regions -- and for the people that depend on them.

More than five miles below the surface of the Pacific Ocean, the temperature is near freezing, there’s no sunlight, and the pressure is more than five tons per square inch. Yet that forbidding zone is home to the deepest fish yet seen — a tadpole-shaped creature known as a snailfish.

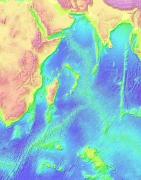

Most of the ocean floor is more poorly mapped than the surfaces of the Moon or Mars. That fact has been highlighted by the search for Malaysian Airlines flight 370, which vanished in 2014. Investigators concluded that it crashed into the southern Indian Ocean. But the search was hampered by the lack of good maps of the ocean floor.

That poor view hinders research as well. The contours of the ocean floor guide currents, and they affect the way different layers of water mix together. So good maps help scientists develop better models of ocean circulation, climate change, and more.

When Europeans began settling in the Americas, they carried diseases that decimated the native populations. Centuries earlier, though, other visitors from the Old World may also have brought a deadly disease to the New: tuberculosis. But these visitors weren’t intent on conquest or searching for gold. In fact, they weren’t even human — they were seals and sea lions that crossed the Atlantic Ocean.