Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

In September of 1938, a monster hurricane roared across New York and New England. Sustained winds topped 120 miles per hour, and a massive storm surge flooded cities and towns. The storm killed about 600 people and, in today’s dollars, caused more than $40 billion in damages.

You can find creatures on the bottom of the ocean that’ll eat just about anything — from the poop of other organisms to minerals that bubble up from below the ocean floor. Even so, the diet of one type of crustacean is a bit of a surprise. That’s because it feeds on something you wouldn’t expect to find on the ocean floor: wood.

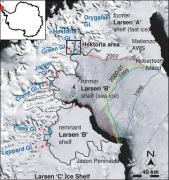

Some giant sheets of ice off the coast of Antarctica are disappearing like ice cubes being emptied from a stack of trays in your freezer. The first tray was emptied two decades ago, a second followed a few years later, and a third may go by the end of the decade.

These “trays” are parts of the Larsen Ice Shelf. It reaches into the Weddell Sea from a narrow finger of land that extends toward South America.

In many human cultures, the elderly have been respected as sources of knowledge and experience. And one non¬-human culture seems to revere its elders as well: a population of killer whales. In fact, they’re most likely to follow an older female when times are tough.

Female orcas can give birth between the ages of about 12 and 40. But unlike many other mammals, which don’t live beyond their childbearing years, female orcas can live into their 80s or 90s.

Treating a headache with a torpedo may sound like overkill, but that’s just what happened in ancient Greece and Rome. Of course, the torpedo wasn’t a projectile like that fired from modern submarines. Instead, it was a type of fish -- a ray that can deliver a powerful electric charge.

Torpedo rays are found in shallow coastal waters around the world. The Atlantic torpedo lives along the eastern and Gulf coasts of the United States, and the Pacific torpedo is found from Baja California to British Columbia.

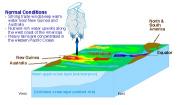

The rise in global temperatures isn’t smooth and even, like turning on a flame under a tea kettle. That’s because it’s a complicated process that involves the atmosphere, the oceans, and other factors.

One of those factors seems to be trade winds over the Pacific Ocean. Weaker winds lead to higher temperatures, while stronger winds tend to cool things down a bit.

When a whale dies, its carcass is a massive buffet for bottom-dwelling organisms. They can strip the bones bare in a matter of months. But the feast doesn’t end there. Tiny worms feed on the bones themselves, carpeting the skeleton in what looks like a giant feather boa.

The first of these bone worms were discovered in 2002, a couple of miles deep off the coast of California. Another dozen or so species have been found since then, in both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

For much of the United States, El Niño is a welcome event. It tends to bring more moderate temperatures to most of the country, and more rainfall to parts of the southwest. It also reduces the number and intensity of tropical storms that hit our coastline. And recent research suggests another benefit: fewer tornadoes and big hail storms across most of the country.

El Niño occurs every few years, when the surface of the eastern Pacific Ocean gets warmer than average. More water evaporates and streams across the U.S., altering weather patterns over millions of square miles.

One of the best ways for biologists to learn about marine life is to tag along for the ride -- to plunge into the ocean depths, or travel on a migration that may cover thousands of miles. Since it’s hard to know how many sandwiches to pack for such a trip, though, scientists use proxies: satellite trackers, video cameras, and other devices.

Many adventurers yearn to “sail the seven seas” -- to ply all the world’s oceans. Well, we have a little bad news for those folks. There aren’t seven oceans. In fact, there’s only one -- the global ocean.

Modern-day maps typically show five oceans: the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, and Arctic, plus the recently designated Southern Ocean. All but the Southern Ocean are at least partially bounded by the continents or by strings of islands, which makes them look like separate bodies of water -- but they’re not.