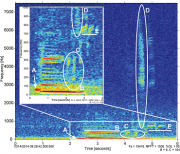

They went looking for typical calls of blue, minke, n, humpback and other whales who live in the area of Mariana Trench Marine National Monument, a nearly 100,000-mile region east of the Philippines near Guam. The team of acoustics scientists from Oregon State University and Cornell University “ ew” an underwater robot 1,000 meters deep to record sounds in the area. But they stumbled upon a mysterious sound they had never heard — or seen — before.

Articles

The Marine Science Institute's monthly column, Science and the SeaTM, is an informative and entertaining article that explains many interesting features of the marine environment and the creatures that live there. Science and the SeaTM articles appear monthly in one of Texas' most widely read fishing magazines, Texas Saltwater Fishing, the Port Aransas South Jetty newspaper, the Flour Bluff News, and the Island Moon newspaper. Our article archive is available also on our website.

Bowhead whales and Greenland sharks can live up to two centuries, and century-old Galapagos giant tortoises are just young adults. But none of these creatures can hold a candle to corals and sponges. Although both corals and sponges look somewhat like plants, they are two very different kinds of animals that can grow to be thousands of years old.

Dining on a jellyfish may not seem too appetizing to most creatures, considering the danger of getting stung. But these gelatinous blobs are a major menu item for various lobster species. The question is: how do lobsters protect themselves from those venomous stingers? Scientists sought the answer in the most logical place: lobster poop. It turns out that lobsters have evolved several adaptations that allow them to consume jellyfish without harming themselves in the process.

Many predators hunt by camouflaging themselves and waiting for unwary prey to swim close enough to become a meal. One species of frogfish managed to hide from scientists, too. Only in 2015 did researchers rediscover this color-changing critter dwelling in tropical and subtropical waters and determine that it was an entirely new genus and species, Porophryne erythrodactylus. What makes frogfish such successful predators is their ability to completely blend into the sponges and corals where they lay in wait, so it’s incredibly difficult for unsuspecting prey to spot them.

Nearly all of the world’s seven sea turtle species are facing a high risk of extinction, in part because of illegal trade of their eggs and shells. Yet scientists still know very little about the lives of these turtles, making it difficult to accurately track their populations and choose successful conservation strategies. One of the most basic tools marine biologists lacked was a way to calculate a turtle’s age — until now. The solution has been right in front of them the whole time, on the backs of the turtles themselves.

The hagfish is one of those animals that scientists aren’t quite sure how to classify. These bottom-feeders have a skull but no backbone. Like lampreys, they have no jaw, but then lampreys do have vertebrae. Hagfish look like eels, but with naked skin instead of scales. They can survive up to 36 hours without oxygen — while their hearts keep beating — and they’ve been around for more than 350 million years, long, long before the first dinosaurs ever walked the Earth.