When a modern-day ship glides across the oceans, it’s guided in large part by satellites -- the Global Positioning System. They reveal the ship’s position to within a few feet.

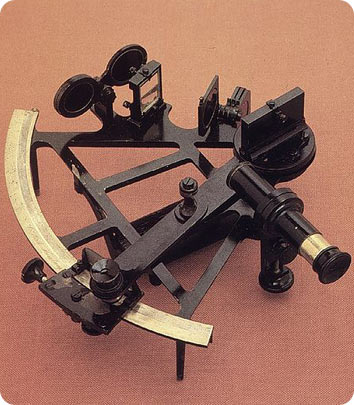

A sextant, used in early coastal navigation. Credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

A sextant, used in early coastal navigation. Credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric AdministrationWhen early explorers began heading across the oceans, though, they were guided in large part by the stars -- a method that often led them dangerously off course.

The earliest sailors were guided by the coastline. When they began to venture out to sea, they relied on the position of the Sun, the ocean currents, and even the birds to keep them on course.

Beginning around the end of the 12th century, they were helped by technology: the magnetic compass. And they soon acquired more technology: devices that allowed them to plot the location of the Sun or the bright stars.

The North Star provided an exact plot of latitude -- the position north of the equator. If the North Star was 45 degrees above the horizon, then the ship was at 45 degrees north latitude. And as explorers ventured south of the equator, they found new stars to navigate by.

For centuries, though, even the best methods of measuring longitude -- the position east and west on the globe -- were inaccurate and hard to use.

The problem was solved in the 18th century, when Englishman James Harrison invented highly accurate clocks. A navigator could then use the Sun and stars to compare the local time to the time at a known point of longitude. The difference revealed the ship’s longitude -- keeping it on track for even the longest voyages.