It’s tempting to think of the oceans as a big mixing bowl -- pour in a little water here and a little there, and it all blends together. That’s not quite the case, though. Water from different sources forms ribbons, sheets, and blobs that tend to stay together for a while.

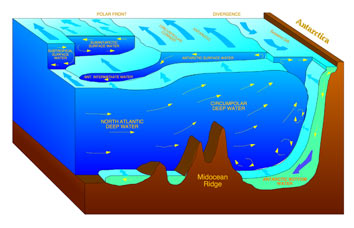

Water masses of the Southern Ocean. Credit: Hannes Grobe, Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, Germany

Water masses of the Southern Ocean. Credit: Hannes Grobe, Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven, GermanyThese structures are known as water masses. Each one forms separately, and is distinguished by a similar temperature and salinity across the entire mass. Those that are colder and saltier are denser, so they sink toward the bottom, while those that are warmer and fresher are less dense, so they stay near the surface.

One example is known as the North Atlantic Deep Water. It forms as the warm water of the Gulf Stream, which loops from the East Coast of the United States toward Western Europe, chills as it reaches the cold climes of the North Atlantic. As the water gets colder it sinks and spreads out a bit. It doubles back toward the south, along the coast of Africa to the Antarctic.

There, some of the North Atlantic Deep Water mixes with the much colder water below the ice around Antarctica. This cold, salty water then flows outward as another water mass -- Antarctic Bottom Water, which fills the bottom layers of most of the world’s oceans.

The different water masses carry heat from one region to another. So any changes in the water masses -- caused by reduced runoff from land, for example, or a change in salinity caused by melting ice -- could have an important effect in the oceans’ ability to regulate global temperatures.