A hidden killer can lurk along the coastline, ready to pull unsuspecting swimmers out to sea. It’s not a great white shark, though —or a creature of any kind, for that matter. Instead, it’s a rip current — a narrow channel of water that flows away from the beach, catching unprepared swimmers.

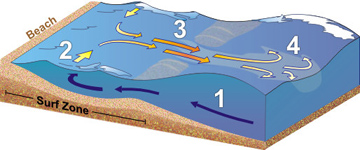

Illustration depicting the steps in rip current formation. Credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Illustration depicting the steps in rip current formation. Credit: National Oceanic and Atmospheric AdministrationRip currents are found along most beaches. They form from the complex interplay of waves, wind, the contours of the sea floor, and other factors. And on some of the most popular beaches — those with gentle slopes and beautiful sand, like those in Florida — rip currents are related to sandbars that are attached to the beach or submerged just offshore.

Waves push water over the sandbars. But the water along the shore can rise only so high before it heads back out to sea. This return flow can either go straight offshore as a weak undertow, or get concentrated in channels that cut through the sandbar. And just as putting your finger over the end of a garden hose produces a more powerful stream, squeezing that much water through a narrow channel produces a strong flow — up to a few miles an hour. During storms, the current can be strong enough to push even the strongest swimmers along with it.

Most rip currents are only a few yards wide. And while many extend just beyond the surf, some may travel for hundreds of yards.

Despite the dangers, some signs can point them out. An example is that the rip current tends to look calmer than the surrounding surf — a sign that can help you stay out of harm’s way.

This episode of Science and the Sea was made possible by Texas Sea Grant.