1913 was a big year for the Norwegian fishing industry — the fleet brought in a record haul of adult herring. Marine biologists discovered something odd, though: Most of those fish had hatched in a single year. The discovery helped change the way that scientists look at fish populations and the focus of their research on fisheries.

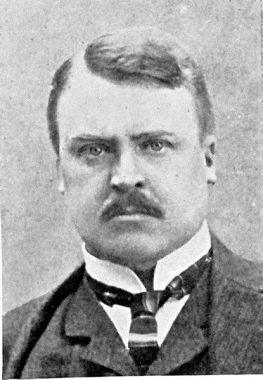

The new idea came from Johan Hjort, a biologist who directed the Norwegian Institute for Marine Research.

The new idea came from Johan Hjort, a biologist who directed the Norwegian Institute for Marine Research.

The catch of herring and cod could vary dramatically from year to year. At the time, the leading idea said the fluctuation was caused by migrations — the fish moved around to find waters of just the right temperature.

But research by Hjort and others showed otherwise. Herring, for example, stayed in a fairly small region of the North Atlantic Ocean.

Hjort found that most of the herring caught by the fishing fleets had hatched in just a few good years. 1904 was especially good. Yet 1904 wasn’t an especially big year for herring spawning. That led Hjort to conclude that the survival of the spawn in a given year depended on what happened shortly after the eggs hatched.

In particular, he determined that the young fish needed to eat right away. If food was plentiful, then many of the hatchlings survived. If not, they starved.

Hjort presented his idea in a book published in 1914. “Fluctuations in the Great Fisheries of Northern Europe” became a hit among his colleagues — and continues to influence research and fisheries management even today.