Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

The coral reefs off one of the islands of Palau are marine acidheads. They thrive in waters that are more acidic than those yet measured for any other healthy reef. That’s of interest because the world’s oceans are becoming more acidic as a result of our changing climate.

The American eel certainly gets around. It can travel from the western Atlantic Ocean to Lake Ontario. And after hanging out in the Great Lakes for a while, it turns around and heads back out to sea.

The ocean surface generally looks pretty flat. It gets choppy in storms, but otherwise we don’t see much difference in elevation. Yet that appearance is deceiving. Hills, valleys, and slopes contour the ocean surface just as they do the ocean floor. And studying those features can help scientists better understand the role the oceans play in our changing climate.

Here’s a tasty little story that’s likely to set your tongue a-waggin’. In fact, it’ll probably make you grateful that you have a tongue to wag at all. It’s the tale of a marine critter no bigger than the tip of your little finger that invades the mouth of a fish and eats its tongue. It then becomes a replacement for the tongue.

The creature has the tongue-twisting name of Cymothoa exigua. It’s an isopod — a type of crustacean. It’s found in the Gulf of California and other waters along the eastern Pacific.

Some relatives of pill bugs have colonized tropical beaches around the world. Yet they don’t get around much — they don’t swim or float in the water. Instead, they may have relied on the motions of the land itself to spread them around the globe.

An evolutionary “missing link” toddled across the chilly landscape of northern Canada at least 20 million years ago. It used its strong limbs and big teeth to devour a duck and a small rodent — its final meal. After it died, it was buried in the sediments at the bottom of a lake. It wasn’t seen again until 2007, when researchers discovered its fossilized skeleton.

Puijila darwini was about three-and-a-half feet long, with a head that resembled a modern-day seal and a body that resembled an otter.

For thousands of years, the people on the coast of what is now northern Peru lived by harvesting the bounty of the Pacific Ocean. They gathered shellfish, and left big piles of shells and other debris on the beach. Those piles helped anchor long, sandy ridges on the beach against the wind and waves, so some of the ridges are still in place today.

Black sea bass has been a popular catch along the East Coast of the United States. Its meat is tasty, and it puts up a bit of a fight, so commercial fleets and recreational anglers alike have gone after it.

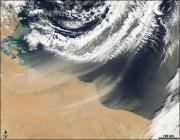

The possible link between global warming and stronger Atlantic hurricanes is complicated. It involves changes in water temperatures, wind speeds, and other factors. It may also involve weather conditions over Africa.

For a big creature with big jaws, the megamouth shark keeps an unusually quiet profile. In fact, it wasn’t discovered until 1976, and only about 60 have ever been recorded.