Radio Program

Our regular Science and the SeaTM radio program presents marine science topics in an engaging two-minute story format. Our script writers gather ideas for the radio program from the University of Texas Marine Science Institute's researchers and from our very popular college class, Introduction to Oceanography, which we teach to hundreds of non-science majors at The University of Texas at Austin every year. Our radio programs are distributed at to commercial and public radio stations across the country.

Penguins may look cool, but they never seem to get cold. And recent research has provided some reasons: tiny holes in their feathers, and a special oil that acts as a sort of antifreeze.Researchers compared the feathers of two types of penguins — the gentoo, which lives in Antarctica, and the magellanic, which lives in the warmer climate of South America.

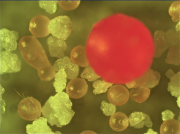

Your shower gel, eye makeup, and even toothpaste may develop a slightly different feel in the years ahead. That’s because the United States has banned one of their key ingredients: tiny balls of plastic known as microbeads.

As the name suggests, most of these beads are microscopic. They’ve been used as abrasives in many personal cleaning products, and as lubricants in many cosmetics. The problem, though, is that when you rinse them off, they don’t stop — they can rinse into rivers, lakes, and all the way into the oceans.

People love sharks. We might be scared of them, but we still love to watch them glide through the water. Most of us watch them on TV, but many prefer to see the real thing — to see their menacing shapes from a boat, or even to plunge in and swim with the sharks.

In fact, shark tourism is big business. And in the next couple of decades, it could become even bigger. As a result, sharks could be worth a lot more alive than dead.

High school science teachers might be looking for some new lab experiments in the coming months. That’s because one of the main supplies for a classic experiment is getting both more expensive and harder to find.

Agar is the gelatin-like substance that’s layered in the bottom of petri dishes. It’s a great material for growing cultures of bacteria and fungi because it stays solid at high temperatures, it’s stronger than gelatin, and the bacteria don’t eat it.

In modern times, salmon from the Pacific Ocean is a delicacy — an expensive dish that’s usually served as a treat — even in areas where the fish is plentiful. In ancient times, though, that wasn’t the case. During spawning runs, tribes and villages caught salmon by the thousands. Many of the fish were preserved, providing nutritious meals during the long, cold winter.

In fact, researchers recently found evidence that settlers in central Alaska were eating one type of salmon about 11,500 years ago. It’s the earliest known instance of people eating salmon in all of North America.

That disturbing packet of goodies that’s stuffed inside many turkeys includes the gizzard — something that few want to eat, but that’s essential to helping the turkey eat. It grinds up food before it passes into the stomach, aiding in the turkey’s digestion.

In fact, the gizzard is a common organ in many types of animals, including some fish and other marine creatures. One is a type of sea slug found in European waters, which feeds on tiny shellfish. And a team of researchers recently dug into its gizzard to find out how it works.

For a guilt-free sport fish that also tastes good, you might consider the dolphinfish, which today is probably better known as mahi-mahi. Even though the numbers caught by both recreational anglers and commercial fishing fleets have increased in recent years, the population seems to be stable. As a result, it’s not on any “endangered” lists. Instead, it’s on many “recommended” lists as a good, sustainable seafood choice.

Beaches are among the most ephemeral natural features on the planet. They’re built by wind and waves, which push grains of sand ashore — a process that can go on for thousands of years. But beaches can disappear quickly — in years, days, or even hours. The everyday action of wind and waves and rain can erode them gradually, while big storms can erase them overnight — bulldozing them back into the sea.

When the Exxon Valdez ran into a reef off the coast of Alaska more than a quarter of a century ago, it created an environmental catastrophe. The tanker released 40,000 tons of crude oil into the water, killing fish, mammals, and a quarter of a million birds.

Yet much more oil enters the oceans every year through daily human activities. Oil from leaking car engines, pipelines, and industrial facilities washes into rivers and streams, which flow to the coast. Small boats leak directly into the water. So do coastal refineries and off-shore drilling platforms.

A rose by any other name may smell as sweet, but it’s certain that a hurricane by any other name can be just as deadly. That’s because the names we call big tropical storm systems are all describing the same thing — a spinning pattern of clouds with strong winds, heavy rains, and deadly storm surges.

In the western hemisphere, once a system’s winds reach 39 miles per hour, we call it a tropical storm and give it a formal name. And when the winds hit 74 miles per hour, we call it a hurricane — from the name of an unpleasant Caribbean god.